Power, released in theaters on January 31, 1986, follows Pete St. John (Richard Gere), a superstar political consultant “hired gun” whose real clientele are not voters but ambitious candidates and the moneyed interests behind them.

Pete is hired to engineer the ascent of an industrialist (J.T. Walsh) into a vacated Senate seat, a job that pulls him into a tangle of manufactured images, media manipulation, and buried secrets.

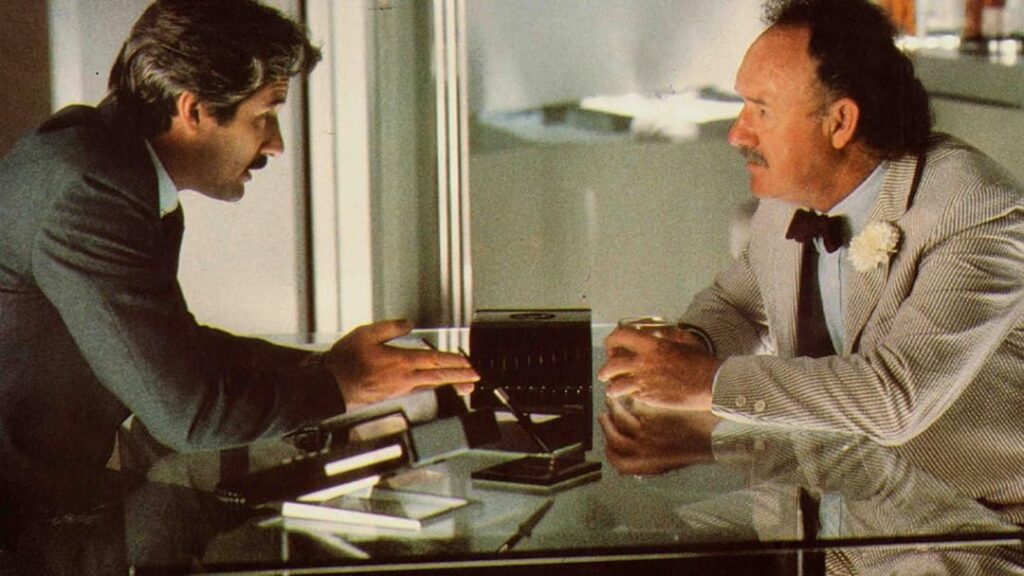

As he clashes with a rival spin doctor (Denzel Washington), disappoints his idealistic ex‑wife (Julie Christie), and faces the disillusioned mentor who first taught him the trade (Gene Hackman), Pete is slowly forced to confront the moral wreckage his “wins” have left behind.

The film unfolds as a political drama more concerned with back rooms and television studios than ballot boxes, charting whether a man who sells everyone else’s story can rewrite his own.

Power plays like a quintessential Lumet chamber piece blown up onto the national political stage: talky, morally knotty, and loaded with actors who can make a monologue feel like a knife fight.

Gere leans into Pete’s slick charm and restless anxiety, suggesting a man who has confused cynicism with wisdom for so long he no longer recognizes the difference.

Around him, Hackman gives the film its bruised conscience, while Christie and Kate Capshaw sketch the emotional collateral damage of a life devoted to spin.

The ensemble bench is deep – E.G. Marshall, Beatrice Straight, Michael Learned, Matt Salinger, Fritz Weaver, Tom Mardirosian – and director Sidney Lumet uses them as moving parts in an elaborate machine that shows how campaigns are built on targeted fear, half‑truths, and carefully staged moments.

The downside is that the script sometimes feels schematic, with themes spelled out rather than earned, and the narrative never quite catches fire the way Lumet’s best work does.

Yet even when the plotting turns predictable, there is a queasy fascination in watching professionals treat democracy as a branding exercise, and Lumet’s unfussy direction keeps the focus squarely on behavior, dialogue, and the corrosive ease with which everyone justifies the next compromise.

Power also captures an intriguing transitional moment for its cast: Gere pushing beyond pure romantic‑lead territory, Washington sharpening the intensity that would soon make him a star, and character actors like Walsh and Marshall embodying the bland, respectable faces of power.

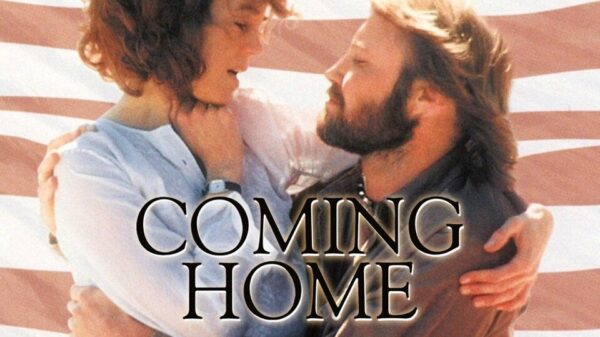

Richard Gere and Gene Hackman in Power (Photo/20th Century Fox)

Reception for Power

Power grossed $1.9 million on its opening weekend, finishing tenth at the box office.

The film would gross $3.8 million in its theatrical run.

Roger Ebert gave Power two and a half out of four stars in his review.

Legacy

Coming after towering achievements like Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network, Power inevitably feels like a minor entry in Lumet’s filmography, but it plays today as a surprisingly modern prelude to the era of permanent campaigning and 24‑hour messaging.

Long before “political consultant” became a cable‑news cliché, the film understood that elections would increasingly be won by people who never appear on the ballot, and that the real drama lies in the moment a true believer realizes he is selling out the ideals that once drove him.

For Lumet, Power may not reach the satiric ferocity of Network or the raw urgency of his 1970s work, but as part of his ongoing obsession with systems—legal, corporate, political—it adds another textured chapter to a career spent asking how decent people lose themselves inside institutions they helped to build.